Pamplona

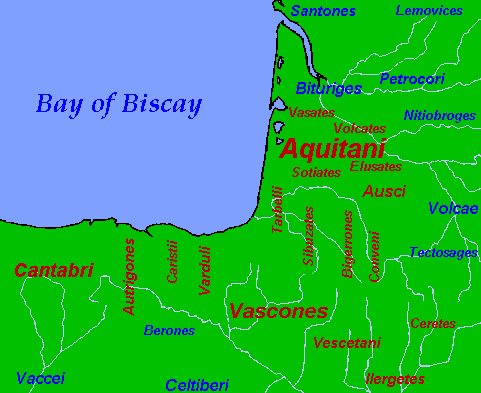

As the North of Vasconia (would-be Gascony mostly) became more romanized and under the influence of Western Frankish Kingdom (eventually known as France), the South would become the political stronghold of Basque identity around the city of Pamplona.

The origins of the

Kingdom of Pamplona are still somewhat shrouded in mystery and legend but it seems clear that the state was product of the battles of Roncevaux which prevented Frankish ambitions to be consolidated. In the South a smaller Muslim realm,

the Banu Qasi emirate of Tudela, supported and was supported by the nominally Christian Kingdom of Pamplona. Religion was not important, freedom was instead.

|

| The Kingdom of Pamplona in the 10th century |

Pamplona was a key and growingly important part of the status quo in the 9th and 10th centuries. At the end of this period, under Sancho the Great, the realm had become the most powerful Christian state in the peninsula, controlling parts of the Hispanic March and all of Castile, and even intervening militarily in Leon on occasion of dynastic disputes.

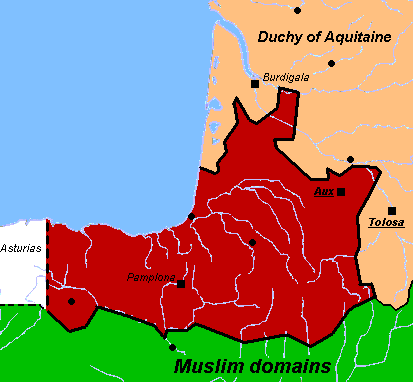

In the following map we can see the extension of the Pamplonese influence c. 1000 CE, under

Sancho (Antso) the Great: Pamplona in red, orange indicates other realms in personal union, while pink indicates states under clear Pamplonese influence at the time.

|

| Domains of Sancho the Great at the beginning of the 11th century |

This period of peace and prosperity would suddenly end in the decade of 1030: in 1031, the last Caliph of Cordoba, the weak

Hisham III died, resulting in the implosion of the Muslim state into a host of small emirates known as

taifa realms. While until then the upper hand was always that of Cordoba, which regularly collected tributes from the Christian realms of the North, suddenly the situation changed radically and the vassals became overlords and raiders of the smallish new Muslim principalities.

A few years later, in 1035, Sancho died and his little personal

empire, was divided among his sons:

García Sánchez of Najera, the eldest legitimate son, inherited Pamplona, Gonzalo got Sobrarbe and Ribagorza, Ferdinand got Castile and the illegitimate son Ramiro was appointed Count of Aragon under Pamplonese sovereignty.

Soon Ferdinand of Castile had invaded Leon, with Pamplonese help (a clear strategical error), and taken the royal crown while Ramiro of Aragon had displaced his half-brother in Sobrarbe and Ribagorza. And soon after these two aggressive spawns were allied against their brother in the throne of Pamplona as well.

Atapuerca and The first partition

For many Atapuerca (from Basque ate: gate and Romance puerco: pig), located just outside Burgos, is just a Paleolithic archaeological site. However it is also a pass between the Duero and the Ebro basins and as such it was upon a time, this time, the Southwestern border of Pamplona.

It was also the site of

the battle in which García Sánchez lost his life in 1054 and the site where the Basque Army rejected the possibility of appointing his brother Ferdinand, the invader, as new king of Pamplona, electing instead by acclamation his teen-ager son: Sancho García

the Noble.

Sancho was in almost perpetual war with Castile for the western territories of Pamplona, sometimes supported by Aragon. Sancho was murdered by his siblings at a hunt near Peñalén in 1076, being Pamplona divided soon after.

Pamplona remained formally independent, in spite of having lost 2/3 of the country to Castile, under the Aragonese monarchy. It was in that time when parts of it began to be known as Navarre, probably from Basque nabarra: the brown (land).

The Restoration

Upon the death of Alphonse the Battler, his will gave all his realms to the Templar Knights. Neither the Parliaments of Navarre nor those of Aragon could agree with such weird idea, so they proclaimed new kings. In Navarre it was

García Ramírez the Restorer, a relative of El Cid, who was soon engaged in another continuous war with Castile for the Western Country.

In 1177, King Henry II of England, who was also Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony (among other things), attempted to mediate between the two kingdoms. In the preserved documents it is clear that Navarre supports its claims on the will of the people, while Castile does on its military might that so useful could be to Christendom.

The mediation failed but two years later a similar peace was agreed: Castile kept Oca, Bureba, Rioja, while Araba and the coast (would-be Biscay and Gipuzkoa) remained under Navarrese control.

Castilian conquest of the West

In spite of all guarantees, in 1199, Castile invaded the Western Basque Country again while the new king, oddly known as

Sancho the Wise, was in Africa in diplomatic mission. The fortified places of Vitoria and Treviño resisted but the king, unable to muster an army apparently, sent the Bishop of Pamplona with the order of surrender. Vitoria did surrender but Treviño fought until the end, reason why it was assigned to a Castilian feudal lord, while the rest of the Western Country was allowed to retain most of their self-rule.

For Castile, access to Basque harbors was important in order to export their wool to Flanders and general trade with Europe. Of course that was also true for Navarre, which had founded the harbor city of San Sebastian not much earlier and retained for some time access to the sea via Hendaia (and would later use Bayonne under treaties). But Navarre lost and that time it was a consolidated defeat, specially as Castile had grown very large at the expense of the Muslim realms of the South.

In order to secure the loyalty of the defeated Western Basques, Castile granted quasi-independence to the three resulting provinces: Araba, Biscay and Gipuzkoa, which retained Navarrese law and self-rule for almost every aspect, being able at times even to negotiate fishing treaties. Importantly the citizens of these three republics were exempt from military service (except temporary territorial militia in case of local invasion) and were granted gentry rights in the territory of Castile (preventing torture specially).

The last centuries of independent High Navarre

The residual Navarre became more and more attached to some of the most dynamic feudal lords of France: the House of Champagne first, the French crown later (separated because of the French law impeding women to inherit, while Navarre allowed this), the House of Evreux eventually as well.

In that time Navarrese Law became codified and Navarre formally became one of the first Parliamentary Monarchies of all Europe, however the power of the King (or regent) was still big and feudalization advanced as a cancer as well.

It was briefly under effective rule of the Machiavellian John II of Aragon, who acted against the law all the time, plotting the final collapse of Navarre in parallel to pan-European imperial ambitions. For that reason he murdered one after the other all his children with Queen Blanche of Navarre being an arch-villain of Basque and European history, able to murder his own children for his megalomaniac ambition (leading to the Habsburgs incidentally).

The trick did not work however because, as King consort, he was not by any means in the line of succession. After all heirs were murdered, the Navarrese Parliament eventually elected a young boy: Francis Phoebus of Foix, a member of the French Royal House, too big a fish for the Trastamara poisonous net... by the moment.

|

| Cesar Borgia, captain of Navarre |

The new dynasty was consolidated under (king consort) Jean d'Albret, a major feudal lord of France who became a relative of Pope Alexander VI by marriage of his daughter with the infamous Cesar Borgia, natural son of the former.

We can see here how the politics and dynasties of Europe in the birth of Modernity all spinned around Navarre somehow. Cesar Borgia, after losing his Italian possessions and fleeing an Aragonese prison, became a commander of the Navarrese Army and died at Biana defending the Basque state against the mercenaries of Aragon.

The invasion of 1512-21

But the Trastamaras did not rest and in 1512 they invaded the country with the pretext of a forgery of Papal bull and the support of England, which controlled Bayonne and readied up to block any attempt of help by France.

|

| Navarre and dependencies at the time of the conquest |

The huge Castilian army had not too much of a difficulty in capturing the small country but another thing was to retain it. Almost as soon as the army had left, the Pamplonese revolted and expelled the garrison, incidentally lead by some

Iñigo (or Eneko) of Loyola.

The war persisted for almost a decade, with several expeditions of Gascon troops from Bearn and other possessions of the House of Navarre, entering the South to aid the people in revolt. However in the end, excess of confidence by the Navarrese general

Asparros, who disbanded the infantry and put siege to Logroño, led to a catastrophe.

The last stand of Southern Navarrese resistance was at Amaiur fortress, in Baztan.

Protestant Navarre: First Basque Literature

The remnant of Navarre, almost devoid of Basque-speaking areas but retaining a large number of feudal possessions in Gascony and France became soon a Protestant state and the leading force of the Huguenot Party in the French Wars of Religion.

Queen Jeanne promoted

a renaissance of Basque language, and, as happened with other Protestant nations, one of the first things to be translated to the vernacular language was the Bible (to both Labourdin Basque and Bearnese Gascon). However even older is the

Linguæ Vasconum Primitiæ, a Basque grammar, as well as some other works.

She was also leader of

the Protestant camp in France. However the main role in this aspect would belong to her son

Henry, who would eventually become King of France (as well as of Navarre) under the condition of renouncing to his Calvinist faith (Paris is well worth a mass). Known as

the good king, he founded the dynasty of the Bourbons and kept all the time Navarre effectively independent. The Kings of France would style themselves

Kings of France and Navarre until the French Revolution and then in the brief Restoration, however, while residual Navarre (with Zuberoa and Bearn) enjoyed some autonomy, it did so as province of France since 1620.

(... to be continued).